科技與神經科學

撰文及考題設計/British Council 英協教育中心 Brian Welter 中譯/陳怡君 (中央社編譯)

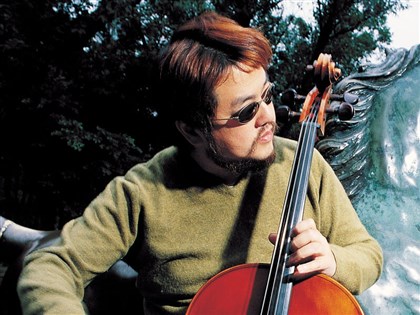

Have you ever looked at a beautiful wood carving of a bunch of grapes or of a small animal and wondered how someone could create it? Or wondered what steps were involved, from selecting the wood to envisioning the final product to planning the process one step at a time?

您可曾驚奇地凝視刻成一串串葡萄或是小動物的木雕,然後好奇這是如何創造出來的?或是從選擇木材到構思成品的過程,究竟需要多少步驟?

This process is a mystery to neuroscience, which is the study of the brain. This research encompasses individual brain cells, called neurons, as well as clusters of neural networks and then, finally, the various sections of the brain that these clusters combine to make. Comprehending this all poses a difficult challenge because a one-to-one relationship between a specific brain part or neural cluster with a specific action, thought, or feeling does not exist. Conversely, many single brain structures are “pluripotent,” which means that they can do many different kinds of jobs, professor Dietrich Stout of Atlanta’s Emory University notes. 這個過程對研究大腦的神經科學來說是個謎。這個研究涵蓋了從稱作「神經元」的神經細胞,以至錯綜複雜的神經網絡,最終組成大腦的不同區域。理解這些極具挑戰性,因為特定大腦區域或神經叢與特定行為、想法和感受之間的一對一關係並不存在。相反地,亞特蘭大的艾莫瑞大學史陶特教授指出,許多單一大腦構造是「多能」的,意思是他們可以執行不同種類的工作。

Not surprisingly, neuroscience has a difficult time trying to understand how we think and learn about technology. This is particularly difficult when the use of a tool is considered. A tool places limits on human actions. A wood carving knife can be gripped and used in only specific ways. The body and brain must adapt to that reality if the knife is to be used in a productive manner. Some basic brain research on macaques, a species of monkey, has shown that they use a tool as an extension of their body. Other research indicates the same for humans.

不意外地,神經科學為了研究我們如何思考與學習科技而傷透腦筋,當考慮到使用工具時更形困難。工具侷限了人類的動作,一把木雕刀只能以特定方式被抓握與使用。身體與大腦必須遷就於「使雕刻刀發揮作用」的現實上。許多關於獼猴的基礎研究指出,牠們已懂得使用工具當作身體部位的延伸;其他研究在人類身上亦有相同的發現。

The neuroscience of how humans use tools and technology raises many complex issues for researchers. Not only must the neuroscience of the actual use of the tool or technology be understood, but also the steps to learning to use the tool in the first place, the pre-use objectives, and, finally, the motivations for a specific project. Added to this, the individual perceives whether he is properly using the tool or not and integrates feedback from other people both at various points in the process and at the end.

在人類使用工具與科技的神經科學研究中,研究人員指出了更複雜的議題。神經科學不僅止於理解工具或科技的正確使用方式,還要「學習」使用的步驟,使用之目的,最後是具體動機。此外, 個體必須了解是否正確使用該工具,並在過程到結束的各階段整合其他個體的反饋。

Thi s i ndicat e s a social component to neuroscience. When learning how to use a tool or new technology, we often imitate what others do. The teaching of how to do a wood carving requires social interaction. Yet how does one learn to imitate a master? No two pieces of wood are exactly the same: One is denser and therefore requires more pressure. Another is older and more brittle, and therefore could break more easily. The master’s carving tool is not exactly the same as the apprentice’s. The two individuals do not have the exact same strength.

這印證了神經科學的社會面向。當學習如何使用工具或新科技時,我們通常去模仿他人。指導如何去雕刻一座木雕需要社會互動,但我們如何去模仿一位「大師」?沒有兩塊木料是完全一樣的,一塊也許比較厚實而需要更多氣力;另一塊也許比較老而脆,因此可能較易擊碎。大師的工具也許和學徒的並非完全一樣。兩人並不擁有一樣的力氣。

Understanding how we learn by imitating seems beyond the capacity of neuroscientists at the moment. Anthropologists – researchers who study human behavior – may provide better insights into imitative learning. One thing anthropologists explain well is how two artists making the same carving are able to arrive at nearly identical end products even though the way to get there varies each time, given countless minute differences in wood, tools, and carvers. Artists, ceramics-makers, sword-makers, you name it, can all arrive at what appear to most of us to be identical products.

理解我們如何透過模仿而學習,似乎並非目前神經科學家所能掌握的。研究人類行為的人類學家,倒是針對模仿學習提出更好的觀點。人類學家能提出很好的解釋,兩位藝術家能經歷不同的時間,無盡分秒形成的差異、包括了木材、工具以及匠師等,卻能殊途同歸,創造幾近相同的成品? 藝術家、陶藝家、鑄劍師等等,皆可以創造出在我們眼中近乎相同的成品。

The two key concepts in the human use of tools, according to Stout, are complexity and organisa¬tion. The professor likens something extremely complex but totally lacking organisation to pixels on a screen randomly lighting up. On the other hand, maximal organisation without any complexity would be the screen where every pixel has the same unchanging color. Both, he observes, are boring and meaningless.

史陶特教授指出人類使用工具的兩大關鍵:複雜性與組織性。教授將其比喻為一面螢幕:極複雜而毫無組織可言的情形就像是隨機閃爍的像素般;另一個極端則是極大化的組織性而毫無複雜性可言,就像一面擁有完全相同顏色的像素構成的螢幕。他觀察到,兩者皆無趣而無意義。

It is the combination of complexity and organi¬zation that make things interesting and that enable innovation to occur, such as when new relationships or connections are made. Higher level complex organisations are still a mystery for neurosci¬ence, including the conundrum of how two carvers with different blocks of wood, tools, and cutting movements can end up with apparently identical items.

複雜度與組織的結合,讓事物變得有趣而使創新成為可能,讓新的連結與關係產生。更高度的複雜性與組織性對於神經科學而言仍是個謎:就像是兩位雕刻家能透過不同的木材、刀工與工具雕塑出相同成品的難題一般。 But at least neuroscientists can be happy about one thing: In the years ahead they will be busy trying to figure all this out.

至少有件事神經科學家會感到高興:未來幾年內他們將會埋首試圖理解其中奧祕。

本網站之文字、圖片及影音,非經授權,不得轉載、公開播送或公開傳輸及利用。

![賴總統談國防、台美與晶片 法新專訪重點一次看[影]](https://imgcdn.cna.com.tw/www/webphotos/webcover/800/20260212/1776x1332_944729421047.jpg)